Hundreds of thousands of Russian officials and security officers have taken part in their country’s invasion of Ukraine, and their level of responsibility for the state’s actions is already being examined through international criminal proceedings. It is assumed that real punishment will come only after a change of power in Moscow — and that everyone implicated in crimes, even if they do not end up in the dock, will at least be subjected to a formal process evaluating their eligibility for continued government service. Notably, the experience of West Germany, where an attempt at a similar type of lustration took place immediately after World War II, shows that a complete ban on employment for those who served the old regime is extremely difficult to implement. Just ten years after the end of the war, many former members of the Nazi party were again working in West Germany’s government institutions, even in leadership positions. Yet this did not prevent democracy from taking root. What proved far more important for preventing any resurgence of authoritarianism was the creation of new legal and political institutions.

Content

Denazification and rehabilitation

Presidents of the Federal Republic of Germany and their ties to the NSDAP

Former Nazis in the West German government

Judges and officials from the NSDAP

Denazification and rehabilitation

After its defeat in World War II, Germany was divided into occupation zones, with the western parts of the country controlled by the United States, Britain, and France, and the eastern sector overseen by the USSR. In both areas, large-scale campaigns of denazification were launched with the aim of removing personnel with a Nazi past from state agencies and public institutions.

In the western occupation zone, special tribunals (Spruchkammern) were created in 1946 to review the biographies of Germans who had in one way or another been connected to Hitler’s NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party). Defendants were classified into five categories: major offenders, offenders, lesser offenders, “fellow travelers” (the term used for those who were not convinced Nazis but, out of fear or career considerations, supported the regime or collaborated with it), and exonerated persons. Penalties were assigned accordingly — ranging from fines and dismissals to internment in denazification camps. By default, the presumption of guilt applied: it was the defendant who had to prove their non-involvement in the crimes of the Nazi regime.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

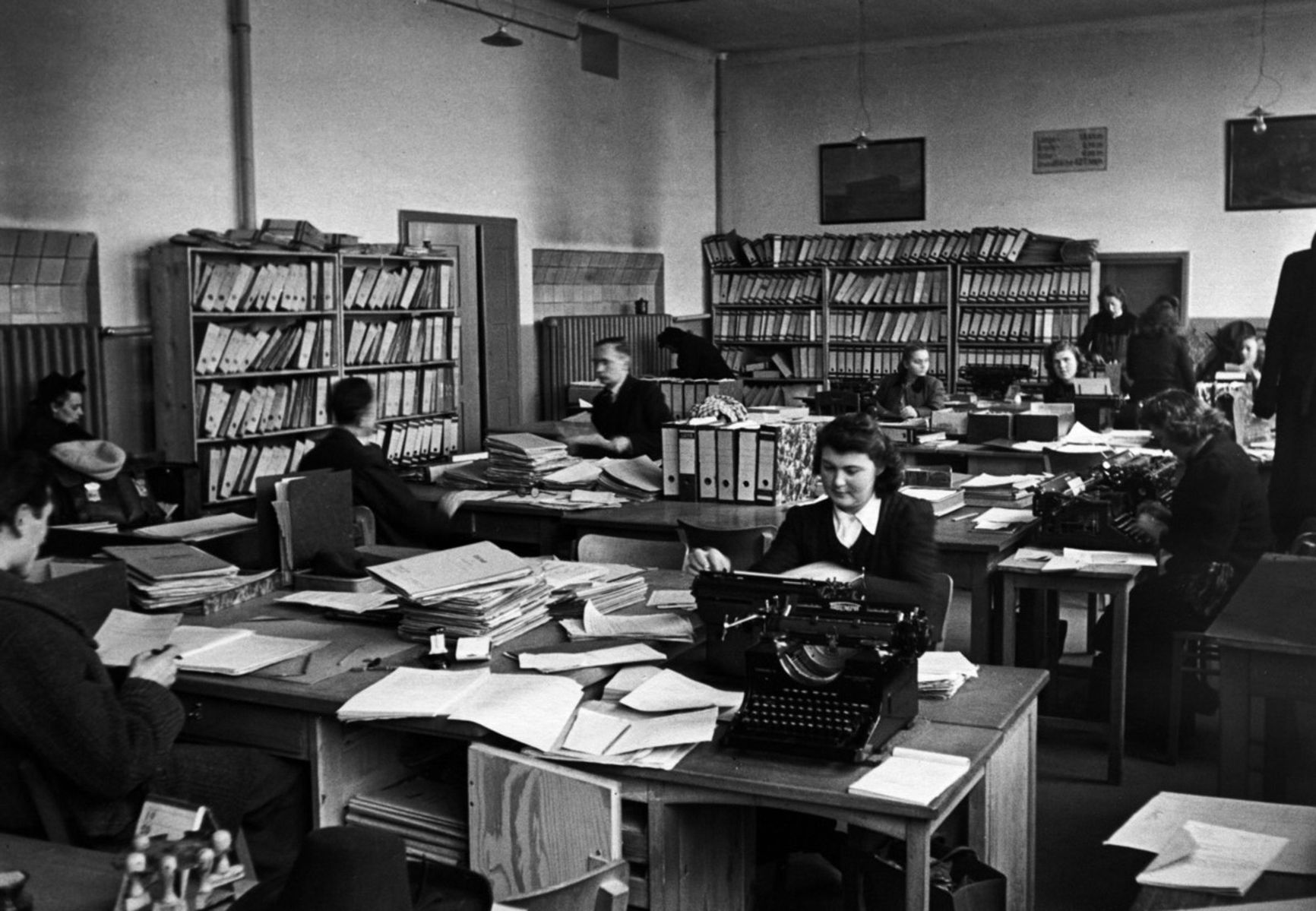

Preparation for a denazification court hearing in Nuremberg, 1947

Denazification affected a vast segment of the German population, but the policy was enforced with particular severity in the American occupation zone. Tens of thousands of officials, judges, teachers, soldiers, and police officers were dismissed or temporarily suspended from their posts. Many were left without a livelihood. Germans perceived the campaign as an unfair and indiscriminate form of punishment, and by the late 1940s, calls in West Germany to “draw a line” under the past and return to normal life were becoming increasingly frequent.

The turning point came in 1951. Faced with a shortage of qualified personnel, mounting public pressure, and growing tensions between the USSR and the West, the Bundestag of the Federal Republic of Germany passed a law that later became known in German society as the “Final Act of Denazification.” It effectively rehabilitated former Reich civil servants, with the exception of those convicted on the most serious charges. Officials, military officers, judges, prosecutors, teachers, and other functionaries regained the right to return to their posts, as well as to receive pensions and social benefits.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

In 1951, the first Bundestag of the Federal Republic of Germany passed a law that effectively rehabilitated former Reich civil servants

In practice, the 1951 law brought the denazification campaign in West Germany to an end. The courts created under the program were dissolved by 1953, and at that time any remaining cases were closed. Officially, denazification policy in West Germany ended in 1954, and a new stage began: the reintegration of former servants of the Hitler dictatorship into the structures of a democratic state, a process later informally termed “renazification.” West German society accepted this new reality without serious protest.

However, it would be mistaken to assume that 1950s West Germany had rehabilitated the legitimacy of its Nazi past. From the very first years of the republic’s existence, the authorities worked to develop legal and institutional mechanisms to prevent the ideology of the NSDAP from returning to the public and political sphere. In 1949, an article was added to the Basic Law of the Federal Republic that prohibited the creation of organizations undermining the foundations of the democratic order. On this basis, the neo-Nazi Socialist Reich Party and the Communist Party of Germany were later banned.

In 1960, amendments to the West German Criminal Code introduced a ban on the use of Nazi symbols, including the swastika, SS runes, and the “Heil Hitler” salute. At the same time, legislation against public incitement to hatred was passed. As a result, by the early 1960s West Germany had built a legal system that made an ideological revanche impossible, even if many former functionaries of the Nazi regime still remained within the structures of power.

Presidents of the Federal Republic of Germany and their ties to the NSDAP

The biographies of the first six West German presidents reflect the diversity of German experiences under the Reich. Some had worked within Nazi structures and fought in the war, while others had supported the resistance to Hitler’s rule.

The republic’s first head of state, Theodor Heuss, who served from 1949 to 1959, had voted in 1933 for the “Enabling Act,” which gave Hitler the power to establish a dictatorship. At the same time, he was not a member of the NSDAP and generally kept his distance from the regime. In 1936, Heuss was banned by that regime from teaching and publishing. Effectively excluded from public life, he continued to write under a pseudonym for the independent Frankfurter Zeitung. Thanks to a shoulder injury, he avoided mobilization and therefore did not participate in any military action.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

Theodor Heuss

The next West German president was Heinrich Lübke, who held office from 1959 to 1969). His activities of the Nazi period remain the subject of debate to this day. During World War II, Lübke held a senior position at the engineering bureau of Walter Schlempp, which was subordinate to Albert Speer, the Reich’s Minister of Armaments and War Production.

Projects carried out by Schlempp’s firm included the construction of military facilities, and it used concentration camp prisoners as a source of forced labor. Documents confirm that Lübke knew about this. Moreover, according to some accounts, he personally requested that more prisoners be sent to the work sites. Later, Lübke claimed that the working conditions had been humane and that he had not subscribed to Nazi ideology.

Lübke’s successor, Gustav Heinemann (president from 1969 to 1974), was one of the few high-ranking West German politicians with a solid anti-fascist background. He had been a member of some formally Nazi organizations, such as the “National Socialist League for the Protection of the Law,” but this was essentially a requirement for anyone who was involved in the legal practice. Despite that formal association, Heinemann participated in the anti-fascist Confessing Church movement, actively supported people persecuted by the regime, and helped those in hiding. He was never arrested by the regime, but he never cooperated with it either.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

Gustav Heinemann

Walter Scheel, president of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1974 to 1979, had a biography more typical of his generation. In December 1942, he was formally admitted to the NSDAP, although after the war he claimed that he had never applied for membership and had not taken part in party activities. Scheel served in the Luftwaffe, fought on the Eastern Front, rose to the rank of first lieutenant, and was even decorated. After the war, his past was considered compromising but not discrediting.

Karl Carstens, who succeeded Scheel in 1979 and remained in office until 1984, had far closer ties to Nazi structures. As early as 1934, he joined the SA stormtroopers of the NSDAP, and in 1940 he entered the party. Carstens later explained this decision as a necessity for preserving his career. During World War II, the future president served in Luftwaffe air defense units, rising to the rank of lieutenant. In his postwar political career, his Nazi past provoked public protests, especially during his campaign for office.

The last West German president to have connections with the Hitler dictatorship was Richard von Weizsäcker, who held office from 1984 to 1994. Weizsäcker came from the old Prussian aristocracy and was not a member of the NSDAP. However, in 1937 he briefly worked as a Hitler Youth squad leader. During the war, von Weizsäcker served in the elite 9th Potsdam Infantry Regiment, took part in campaigns against Poland and the USSR, reached the rank of captain, and was wounded. After the war, he defended his father, diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker, at the Nuremberg Trials, and then began a successful political career. His career arc serves as a kind of symbol for the path followed by the country as a whole: 1985, Weizsäcker became the first West German president to openly call May 8, 1945, a “day of liberation” in an official speech, a landmark moment in Germany’s reckoning with its Nazi past.

Former Nazis in the West German government

The first government of the Federal Republic of Germany, headed by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (who served from 1949 to 1963), symbolized the new state’s early attempts to break free from the Nazi past. Until the completion of denazification in 1953, Adenauer’s government did not include a single former member of the NSDAP, and the chancellor himself was one of the few senior West German politicians who had consistently kept his distance from Nazism without going into exile or being imprisoned.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

Konrad Adenauer (left)

Nevertheless, after 1953 at least 13 former Nazis entered Adenauer’s cabinet — and not only formal NSDAP members, but also more notorious figures. Among them was Gerhard Schröder, who had joined Hitler’s party in 1933, worked as a lawyer in Reich structures, and after the war went on to serve as minister of defense, foreign affairs, and the interior. Another such figure was Minister for Refugee Affairs Theodor Oberländer, a participant in the “Beer Hall Putsch” and an accused war criminal who had fought on the Eastern Front. (Protests eventually forced Oberländer to resign.)

The inclusion of such figures in government was largely explained by the shortage of qualified specialists and the urgent need to rebuild state institutions amid a growing confrontation with the Eastern bloc. Under these circumstances, priority was given to professional expertise and loyalty to the new regime rather than to biographical details from the country’s Nazi past.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

The recruitment of ex-Nazis into government was largely explained by the shortage of qualified personnel and the urgent need to quickly rebuild state institutions

The government of the next chancellor, Ludwig Erhard (1963 to 1966), showed even greater continuity with the prewar elite. Erhard himself was not a member of the NSDAP, but under the Nazis he worked as an industrial consultant and took part in drafting economic plans for the occupied territories.

Erhard’s first cabinet (1963-1965) contained no fewer than nine ministers who had previously been members of the NSDAP, including Walter Scheel, Kurt Schmücker, and Paul Lücke. In his second cabinet (1965–1966), there were eight such ministers. Erhard’s rule marked the final consolidation of the practice of integrating former Nazis into West Germany’s political elite. Over time, however, this approach attracted growing criticism from within West German society.

Kurt Georg Kiesinger, chancellor from 1966 to 1969, had joined the NSDAP in May 1933, and starting from 1940 he worked at the Reich Foreign Ministry, where he was involved in the production of radio propaganda. After the war, Kiesinger was interned, underwent denazification, and was classified as a “fellow traveler.” An open letter from Günter Grass called for Kiesinger’s candidacy to be rejected. However, historians later found no evidence of Kiesinger’s direct involvement in the crimes of the Nazi regime.

Willy Brandt, who served as chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1969 to 1974, was one of the few top-level politicians who had actively participated in the anti-fascist resistance. In 1933, after Hitler came to power, he emigrated to Norway, where he continued his struggle against the regime as a journalist and representative of the socialist movement. During World War II, after being stripped of his German citizenship, Brandt lived under a pseudonym and worked with the Norwegian resistance. After the war, he returned to Germany, serving as a member of the Bundestag and mayor of West Berlin. A biography completely free of collaboration with the Nazis lent special weight to his “Ostpolitik” initiative aimed at improving relations with the Eastern Bloc, and his symbolic gestures of reconciliation included a famous episode in which he knelt before the monument to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

Willy Brandt kneeling in Warsaw, 1970

At the same time, Brandt’s cabinet included people with far more complicated pasts. At least nine of them had once been members of the NSDAP, including Economics Minister Erhard Eppler and Minister of Posts and Telecommunications Horst Ehmke. Some had joined the party at a young age or became members automatically through official channels, circumstances that nevertheless remained a matter of fierce political debate in postwar society.

Helmut Schmidt, chancellor of the Federal Republic from 1974 to 1982, was not an NSDAP member, but like many of his peers, he had taken part in Nazi youth organizations and fought with the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front, including in the siege of Leningrad. Schmidt’s government gradually moved away from the practice of integrating former Nazis into positions of power, though his cabinets still included ministers who had formally been members of the NSDAP — four in the first and second iterations and three in the third. Unlike in the 1950s and 1960s, such biographies were no longer hushed up, and each case was discussed in the media.

Helmut Kohl, chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and later of reunified Germany from 1982 to 1998, belonged to the late 1930s generation. During the Nazi dictatorship, he was still a child and was formally enrolled in the Hitler Youth after mandatory membership was introduced in 1940. In the final months of the war, at age 15, Kohl was drafted into the Volkssturm, but he never reached the front. Due to his age, he could not have been an NSDAP member or a Wehrmacht soldier, marking the end of the line for chancellors who had directly participated in the events of the Hitler years.

Nevertheless, Kohl’s early governments still included ministers with a Nazi past: in his first cabinet in 1982, there were at least six, including influential politicians such as Hans-Dietrich Genscher (foreign minister) and Friedrich Zimmermann (transport minister). Only in his fifth cabinet, formed in 1994, did former NSDAP members completely disappear. As such, Kohl’s tenure served as a symbolic transition to a new generation of leaders who had no connection to the dictatorship.

Judges and officials from the NSDAP

As denazification policies in West Germany softened, many judges with a Nazi past returned to the bench. In the British occupation zone, as early as 1948 around a third of court presidents and the majority of directors and advisers in state judicial bodies had previously been NSDAP members. Moreover, in the 1950s, the share of former National Socialists in some West German courts exceeded that of 1939. By 1956, around 80% of the judges in the Federal Court of Justice had previously worked in the Nazi-era justice system.

By 1966, 10 out of 11 federal prosecutors had been NSDAP members during the dictatorship. The last prosecutor with a Nazi past did not leave office until 1992.

In government ministries in the early postwar years, former NSDAP members also predominated. An expert report prepared in 1948 for the future Federal Ministry of the Interior noted that finding “clean personnel” was virtually impossible: out of 26 candidates for the ministerial post, only one had no ties to the Nazis. By 1953, just four years after the founding of the Federal Ministry of the Interior, over 40% of its staff consisted of former members of the Nazi party.

A similar situation was observed in the ministries of economics, food and agriculture, and foreign affairs. In the Ministry of Justice, the share of staff with a Nazi past reached 75%. In the Chancellery, nearly 20% of senior officials had served under the Nazi regime — as officers, ministry employees, or members of occupation administrations.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.

In 1948, of the 26 candidates for the post of Federal Minister of the Interior, only one had no ties to the Nazis

In the second Bundestag of 1953, 129 out of 487 deputies were former NSDAP members. There was even a joke in West Germany: “After the war, there were more party comrades in the ministry than before it.” An independent commission of German historians studying Nazi participation in the ministry concluded that the joke was not far from the truth.

Such personnel continuity at the federal level persisted for decades. Many former functionaries of Nazi Germany continued their careers in the structures of the Federal Republic with little hindrance. The democratic state built after the fall of the Third Reich did not share the rhetoric or values of the Nazi past, but the biographies of those who shaped its government, courts, and ministries often overlapped. And yet, the republic did not deviate from its democratic course.

The process of coming to terms with and distancing itself from the Nazi past was slow, difficult, and often involved compromises. In the long term, however, it was the resilience of democratic institutions, public debate, and generational change that made it possible to gradually phase out the old cadres and reevaluate history.

A movement within German Protestantism that opposed Nazi efforts to interfere in religious matters and that resisted attempts to create a regime-controlled “Reich Church.”

A political course initiated in the late 1960s aimed at improving West Germany’s relations with the USSR, Poland, and other Eastern Bloc countries by recognizing postwar borders and establishing peaceful coexistence.

A militia created by the Nazis in 1944 from elderly men and teenagers, intended to defend Germany in the final stages of the war.