An organization representing victims of abuse by priests is urging the new Pope, Leo XIV, to take a firm stand against pedophilia in the Catholic Church — and to demonstrate his commitment by setting up a fund to help survivors. Activists point out that, when the current pontiff was a cardinal in the United States, his diocese often looked the other way in such cases and never launched full-scale investigations. At the same time, Leo XIV is credited with playing a key role in dismantling one of Peru’s most notorious Catholic pedophile sects. Still, reports of rape and abuse keep surfacing from countries where the Catholic Church holds strong influence. For survivors, the road to justice is painfully long — sometimes stretching out for decades — and victories are rare. The previous pope, Francis, also faced criticism for his lenience towards priests accused of abuse. In his own homeland of Argentina, the future Francis declined an opportunity to pursue a pedophilia case. Now, many are hoping the new pope will break with that tradition: listen to victims, open up the Church archives, and cooperate with the courts.

Content

Openness policy?

“He chose the most vulnerable”

When the pope didn’t help

Life in fear and shame

A New Hope

Openness policy?

Francis, Leo XIV’s predecessor, was the first pope to publicly acknowledge the crimes of pedophile priests. One of his final acts was to dissolve Sodalicio, a powerful Peruvian religious organization that had become, in effect, a totalitarian sect in which physical, psychological, and sexual abuse were the norm. Robert Francis Prevost — now Pope Leo XIV — spent many years serving in Peru, and the shutdown of Sodalicio is widely seen as one of his key achievements.

In late June, after taking the papal mantle, Prevost sent an open letter to the Peruvian journalists who had exposed Sodalicio’s crimes, thanking them for their courage. Those journalists had been targeted with threats and harassment from colleagues who had been bribed to smear them. “We need journalists to fight against sexual violence,” the pope wrote in a tone many saw as surprising for the Vatican. After all, for much of the Church’s leadership, simply speaking out remains a struggle.

“He chose the most vulnerable”

On July 1, Argentina’s Supreme Court — the highest court in the home country of the late Pope Francis — closed the case against former Catholic priest Justo José Ilarraz, citing the statute of limitations. In 2018, Ilarraz had been sentenced to 25 years in prison for sexual abuse and the corruption of seven boys between the ages of 12 and 14. His crimes spanned nearly a decade, from 1985 to 1993, during which he preyed on seminarians under his care.

At the time, a 40-year-old Ilarraz was in charge of discipline and spiritual guidance for the youngest students at a Catholic seminary in the Argentine city of Paraná. The boys, often from poor but devout families, entered the seminary right after primary school — at just 12 or 13 years old. They lived on the premises and were allowed to visit their families only once every two or three months. Many dreamed of becoming priests.

“We were naïve boys from rural areas, used to working the fields with our parents,” survivor Fabián Schunkr recalled in an interview with Argentine television. “Ilarraz chose the most vulnerable. He would visit their families, get to know them, and knew exactly who was being beaten at home or whose father was an alcoholic. He gained trust slowly — he would hug you, sit on the bed in the shared dormitory with 30 or 40 kids, talk to you, and start touching you. That’s how it began.”

According to Schunk, several dozen boys suffered abuse at Ilarraz’s hands. But only seven of them — including Schunk — found the strength, years later as adults, to go to the police and testify in court.

Several dozen teenagers suffered abuse at Ilarraz's hands, but only seven of them found the courage to go to the police — and only years later

“He would climb into the boys’ beds and molest them. Many were afraid to sleep,” recalled former seminarian José Francisco Dumoulin, a witness in the case. Another victim, José Riquelme, told the court how Ilarraz approached him — Riquelme was fourteen at the time — after a shower. Ilarraz began drying him off, touching his genitals, and said, “There’s nothing wrong with this; it’s just another expression of our friendship.”

According to Fabián Schunk, the priest gave his victims gifts and invited them to his room, where he treated them to drinks and food that were unavailable to other seminarians. He also took great care to ensure his harassment remained secret: “Many victims recalled how they went home for the weekend with a firm resolve to tell their families everything,” Schunk recounted. “But when they arrived, they found Ilarraz sitting at the dinner table with their parents. If he noticed that one of the boys could no longer stay silent or endure it, he would take him to the chapel and make him swear an oath of friendship before an image of the Virgin Mary.”

Fabián Schunk has no doubt that other priests, including much more senior ones, were well aware of Ilarraz’s behavior — multiple complaints had been made against him. This is why, in 1993, the priest was transferred — first to the Vatican for a year, and later to Tucumán, a different Argentine province.

A criminal case against Ilarraz was opened in 2012. He was suspended from ministry, but he was only defrocked in December 2024, six years after his conviction. Ilarraz never admitted guilt and, throughout those years, claimed that his former students had “conspired against him out of jealousy and envy.”

Due to health issues, for the past seven years Ilarraz had been serving his sentence under house arrest. Now, he walks free. The Supreme Court’s decision does not acquit him, but it does halt his punishment. The former priest’s victims and their families — some of whom had been lodging complaints about him since the 1990s — plan to take their fight to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in hopes of securing his arrest.

“Going to court in Argentina is expensive, and most survivors of abuse by priests are not wealthy — they struggle to afford legal representation,” said Liliana Rodríguez, a psychologist with the Argentine Network of Survivors of Church Abuse, in a comment to The Insider. “The Church pays for its priests’ lawyers for years. They all follow the same playbook: drag the process out as long as possible, filing appeal after appeal, until the victims are exhausted and broken down psychologically. And they often argue that what happened wasn’t abuse by an adult against a minor, but a romantic relationship entered into by mutual consent.”

The lawyers often argue that what happened wasn’t abuse by an adult against a minor, but a romantic relationship entered into by mutual consent

The Argentine Network of Survivors of Church Abuse has been active for more than 12 years, bringing together around 500 survivors — men and women alike, including former nuns and seminarians — along with volunteer lawyers and psychologists. They help victims get through the most difficult moments and, if they choose, prepare statements for the prosecutor’s office.

According to psychologist Liliana Rodríguez, many survivors keep their trauma secret for years, even decades. “Clergy who commit sexual abuse against children and teenagers have a lot in common — I say this from personal experience,” she explained. “I’ve taken part in many trials and read numerous expert reports. These people know exactly what they’re doing. They’re always charismatic, skilled manipulators who gain the trust of victims and their families, weaving their ‘web’ slowly and carefully. In small towns, everyone usually knows the priest. How can parents suspect someone who performed the funeral for your grandmother, officiated your aunt’s wedding, and comes over for Sunday lunch? In that situation, how can a 13- or 15-year-old boy or girl bring themselves to talk about being molested? Who would believe them? There’s fear, shame, and guilt.”

The psychological toll is often long-lasting. Survivors may struggle with a sharp drop in school performance, bed-wetting, and chronic insomnia that lasts for years. Some resort to self-harm, inflicting cuts or burns. Many try to suppress their memories, but they resurface with renewed pain when the survivor becomes a parent and begins projecting their own past onto their children. Rodríguez noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people reaching out to the network surged, as survivors found themselves trapped at home with the darkest ghosts of their past.

When the pope didn’t help

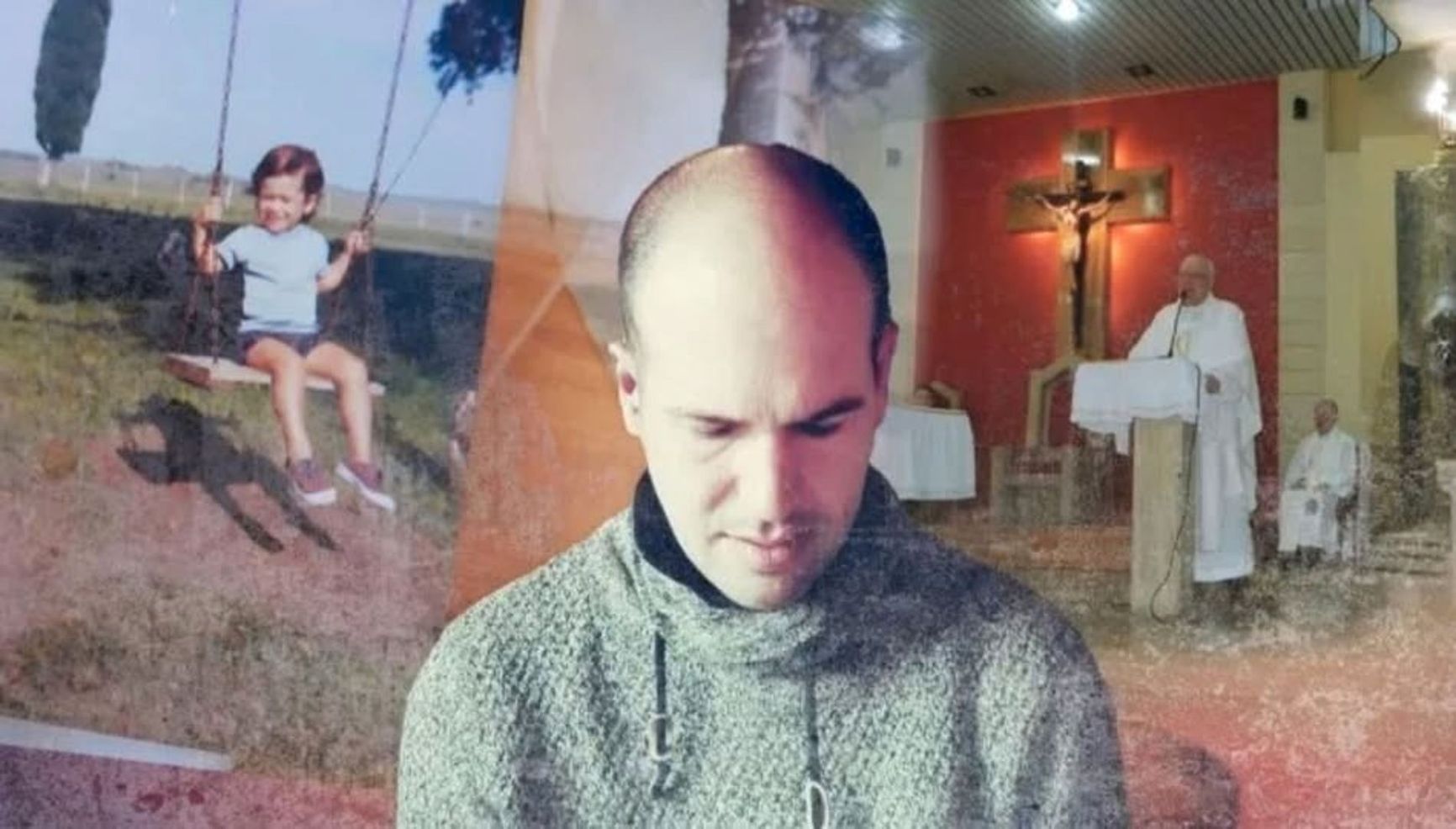

Stress — or even something as simple as a smell — can unlock deeply buried memories from early childhood. That’s what happened to Sergio Decuypere from Paraná. His story is told in detail in the recently released Argentine documentary Three Crosses. For years, Sergio was haunted by the same nightmare: as a five-year-old, in his grandparents’ house, he would walk up to the bathroom door. Behind the door, something terrible was happening. And then the dream would abruptly end.

Sergio Decuypere

When he turned 41, the missing piece came back: inside that bathroom, he had been sexually abused by his uncle, José Francisco Decuypere, a well-known priest in Paraná. The shock of recovering that memory was so severe that Sergio had to quit his job, spending all his savings on psychological and psychiatric treatment. He now lives in Spain.

In 2019, through a priest he knew, Sergio managed to send a letter to Pope Francis. The pontiff called him personally and said he believed him, but Francis asked that Sergio not speak about his uncle — who by then was very elderly and suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. The request applied not only to conversations with journalists, but also with Sergio’s own parents, for whom the truth would be devastating.

Francis advised him to place his trust entirely in the bishop of Paraná. That same year, Sergio gave testimony for an internal Church investigation and met with Francis at the Vatican. According to Sergio, the pope seemed visibly irritated — “as if people were demanding that he bring every accused priest to the square and execute them publicly.”

The pope seemed visibly irritated

Neither the letter, nor the phone call, nor the personal meeting with the head of the Catholic Church moved the case forward. “What hurt me most was the slowness of the process,” Sergio admitted. In September 2020, he stopped following Francis’ advice, spoke publicly about the case, and filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office against his 85-year-old uncle. According to Sergio, several of his uncle’s other victims contacted him afterward. Argentine judges, however, refused to take up the case, citing the statute of limitations.

Still, Sergio Decuypere did not give up. He wants the Catholic Church to officially recognize him as a victim of sexual abuse by a priest and to pay him compensation — a precedent he believes would be significant for all survivors. To this day, he has been unable to get any clear response from the Vatican regarding the internal Church investigation.

Psychologist Liliana Rodríguez says members of the Argentine Network of Survivors of Church Abuse never believed in the previous pope’s fight for justice. From 1998 to 2013, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio — the future Pope Francis — had served as Archbishop of Buenos Aires and head of the Catholic Church in Argentina. According to Rodríguez, he acted a lot like most of the rest of the high-ranking clergy: he shielded those involved in scandals and helped transfer them to serve elsewhere.

“When Bergoglio became pope, he took a series of ‘cosmetic’ steps for show,” Rodríguez said. “He spoke beautifully, said many important things, but in essence did absolutely nothing. The Catholic Church sees sexual abuse as a sin and the priests who commit it as ‘rotten apples.’ They are called on to be forgiven, and the harshest penalty they face is removal from the priesthood. We, on the other hand, are convinced that this is a criminal offense that must be punished accordingly.”

According to the psychologist, if the Vatican truly wanted to change the situation for the better, it would open up all of its archives and willingly cooperate with law enforcement investigations. For now, she says, the Church continues to do everything it can to evade responsibility.

Life in fear and shame

One of the most high-profile trials involving Catholic priests in Argentina took place during the papacy of Francis, while the crimes themselves occurred during his time as archbishop. In August 2024, Argentina’s Supreme Court upheld the conviction of priest Horacio Corbacho: 45 years in prison for sexual abuse and corruption of minors at one of the branches of the Instituto Antonio Próvolo, a network of Catholic boarding schools for deaf and hard-of-hearing children in the province of Mendoza.

Another defendant in the case, Italian priest Nicola Corradi, had been sentenced to 42 years in prison; he died under house arrest in 2021 at the age of 84. Corradi served as head of the boarding school, with Corbacho as his deputy. The school’s gardener, Armando Gómez, was sentenced to 18 years for the abuse of two minors.

The Provolo Institute case came to light in 2016 when sign language teacher Luis Battistelli approached members of Mendoza’s provincial parliament, asking for help in enabling former students to file prosecutorial reports regarding the abuse they had suffered at the boarding school between 2004 and 2016. The court established evidence of three dozen instances of abuse against children. The youngest of the victims was under the age of five.

The Provolo Institute Trial

“Priests threatened to expel the children from the boarding school if they spoke out,” prosecutor Gustavo Stroppiana said during the trial. “Many of these kids came from slums, and the institute was like a luxury hotel to them. They were threatened with trouble for their families. Even after leaving the school, its former students lived in fear and shame.”

According to the victims, Corradi and Corbacho threatened to kill their mothers, and the priests forced children into sexual relations with one another. “My son saw them molest the boy who later raped him. He’s still terrified of Corradi,” said Cynthia Martínez, mother of one of the survivors.

Joel, a former student at the boarding school, told journalists during the trial that the abuse always happened at night, and that hearing-impaired students were deliberately forced to remove their hearing aids so they wouldn’t wake up from the screams. To make communication with their families as difficult as possible, priests forbade the children from using sign language, insisting that they would eventually be taught to speak aloud — this was supposedly the institute’s unique teaching method.

During the trial, it emerged that Nicola Corradi had abused students at the Provolo Institute’s central branch in Verona before being transferred to Latin America in the 1970s, and after that, he abused students at the boarding school in La Plata. The Vatican knew about this pattern but simply continued transferring the pedophile from one children’s institution to another. How did Francis respond to the scandal? In 2017, months after the criminal case was opened and the priests were arrested in Argentina, he ordered an internal Church investigation to begin.

The Vatican knew about abuse but still transferred the pedophile from one children’s institution to another

At the moment, at least ten Catholic priests in Argentina are serving lengthy prison sentences for the sexual abuse of minors. According to the Network of Survivors of Church Abuse, survivors have filed around a hundred lawsuits against clergy over the past 15 years, but most of these cases were dismissed due to the statute of limitations.

At least the problem is unlikely to repeat itself. As psychologist Liliana Rodríguez notes, today’s Argentine children and teenagers are better equipped to face such threats than previous generations were — mainly thanks to the comprehensive ESI sex education program, which was introduced in kindergartens and schools in 2006. The increase in media attention to scandals and trials has also led more parishioners to cooperate with investigators, something that rarely happened in decades past. Still, when asked whether members of the Network of Survivors have any hope for a change under new Pope Leo XIV, Rodríguez replied with skepticism: “Honestly, we have no hope for change within the Catholic Church.”

A New Hope

Leo XIV lived in Peru for more than 20 years, became a bishop there, and received Peruvian citizenship in 2015. The Peruvian Survivors Network — a civil association uniting people harmed by abuse within the Church — is much more optimistic about the new pontiff. The network is headed by José Enrique Escardo, who in 2002 was the first to publicly expose the physical, psychological, and sexual abuse inflicted for decades on minors and other students within Sodalicio.

Founded in Peru in 1971, Sodalicio included both laypeople and clergy. By 2010, branches existed in 25 countries worldwide, with membership reaching as high as 20,000. The organization received official Vatican recognition under Pope John Paul II, and Sodalicio’s influence was so great that in 2005, Pope Benedict XVI invited its founder to the General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops at the Vatican.

Pope Francis Announces the Dissolution of Sodalicio

In early 2025, Francis took one of the final major decisions before his death: following an internal Church investigation, he officially disbanded Sodalicio — a demand survivors had been making for over two decades. Cardinal Prevost, now Pope Leo XIV, played a significant role in this process, according to former members of the sect. Before its dissolution, Sodalicio was forced to acknowledge that 98 of its members had been victims of abuse — a group that included minors aged 11 to 17.

“Now, with Leo XIV elected as the new pope, I can rest assured that we have someone who will continue the reforms Francis began and who is deeply connected to our country and especially close to the Survivors Network and those harmed by Sodalicio,” said José Enrique Escardo, head of the Survivors Network.

In 2021, the Spanish channel RTVE released the documentary The Sins of Sodalicio (Los pecados de Sodalicio), which chronicles the organization’s history. Interviewees include former members José Enrique Escardo and journalist Pedro Salinas — a journalist who authored the investigative book Half Monks, Half Soldiers (Mitad monjes mitad soldados).

Sodalicio was founded in 1971 in Lima by Luis Fernando Figari, an “ultra-conservative layman.” At a time when many priests in Latin America supported a more liberal course — democratizing the Church, serving the poor, and living modestly — Figari held the exact opposite views. Teaming up with several priests and laypeople, he exclusively sought boys from Lima’s wealthy Catholic families for Sodalicio.

Preference was given to blond-haired students with blue, gray, or green eyes. Behind a strict religious façade, Figari effectively created a totalitarian cult — one that brought him substantial profits.

Figari essentially created a totalitarian cult — one that brought him substantial profits

According to Escardo, the hunt for suitable teenagers was conducted in private Catholic schools. Figari told high school students that he possessed supernatural abilities and communicated directly with God. He also claimed to be able to see symbols of the «chosen ones» in the irises of their eyes. “It was the perfect pitch for teenagers: your family doesn’t understand you, but we do; you’re special,” Escardo recalled.

On one hand, the leaders of Sodalicio did everything they could to distance the boys from their families; on the other, they eagerly accepted gifts from wealthy relatives of their chosen ones — for example, a large plot of land in Lima, which Figari turned into a private cemetery, profiting handsomely from it without paying taxes. Sodalicio built connections both in secular and ecclesiastical circles. Its social prestige and image of “chosenness” gradually grew stronger.

Over time, the society’s rules became increasingly strict: the new slogan, “he who obeys does not err,” demanded total submission from its followers. “One day you woke up and realized you no longer had a family, friends, or girlfriend — only Sodalicio,” recalled journalist Pedro Salinas.

Teenagers were taken to rural areas, where they were barely allowed to sleep. While there, they were fed an austere diet, compelled to wash with ice-cold water, forced to exercise to exhaustion, and humiliated frequently — ordered to stand in line and undress, made to fight one another, and molested. According to Salinas, their minds were so thoroughly manipulated that no one complained. They believed they would become almost superhuman.

This went on for years. Figari and his inner circle grew wealthy and did whatever they wanted with hundreds of followers.

Teenagers were taken to rural areas, where they were barely allowed to sleep, forced to wash with ice-cold water, exercise to exhaustion, given little food, and humiliated

The first to speak out to journalists about what was happening inside Sodalicio was José Enrique Escardo, in the early 2000s. Later, he recounted how Figari’s close associates launched a full-scale campaign of harassment against him — orchestrating his repeated dismissals from various jobs. The same fate befell journalist Pedro Salinas and his co-author after they published the investigative book Half Monks, Half Soldiers in 2015.

The leadership of Sodalicio wielded enormous power in Peru and used every tool it possessed — threats, paid media smear campaigns, fabricated criminal cases — in an effort to silence survivors, journalists, and human rights activists. Figari himself has lived in Rome since 2015 and is banned from returning to his homeland. But despite dozens of complaints from survivors, Peru has yet to hold a single trial related to Sodalicio. Nevertheless, many of the victims remain deeply hopeful that this time the Vatican will act more decisively, and that the pope will come to their aid.