Since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the destruction of 1,300 schools has been confirmed, with an additional 3,798 damaged. Hundreds of students have transitioned to a hybrid learning model due to the persistent threat of missile strikes. In frontline cities, direct teacher-student interaction has become nearly impossible. However, the authorities in Kharkiv have devised a solution. Since autumn, classes have been conducted in subway stations, resulting in the establishment of Ukraine's first underground school. The Insider had the opportunity to interview parents and teachers of these “underground” students in Kharkiv. The children, deprived of a regular social life during the pandemic — and then the war — are being educated not only in core subjects like the Ukrainian language and mathematics, but also in recognizing explosive objects and in stress management techniques.

Content

Learning online, in shelters, and in the subway

“When the classroom is quiet and the children are writing, you can hear the train noise”

Wartime curriculum

Learning online, in shelters, and in the subway

Due to the relentless rocket attacks on civilian infrastructure in Ukraine, traditional schooling has become impossible. Some students have shifted to online learning — whether full-time or as part of a hybrid model — while others have simply grown accustomed to attending classes in proximity to bomb shelters, retreating below ground in the event of an air alert.

To mitigate the risks, Ukrainian authorities are tailoring the form of education to suit the safety concerns and preferences of parents in each region. In areas distant from the front lines, schooling continues within the confines of traditional school buildings. Ahead of the academic year, Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal announced that specialized shelters had been established in 68% of the country's educational institutions for this purpose. For instance, despite the threat of longer range drone and missile attacks, face-to-face instruction remains the norm for most schools in the capital Kyiv. Alternatively, some regions opt for a blend of in-person and online instruction — as in Dnipro, which is much closer to the trenches in the south. However, in regions like Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, and Donetsk — where school buildings often fall within Russian artillery range, online education is the only method being utilized.

In 2023, authorities in the Kharkiv region embarked on an experimental project aimed at allowing local children to socialize in an educational setting without putting them in physical danger: opening school classes in subway stations. Anna Neelova, an elementary school teacher who joined the initiative, told The Insider that despite initial doubts from both educators and parents, the endeavor has proven remarkably successful:

“Many tried to dissuade me, but over the two years of living in this setup, I've felt increasingly connected. A teacher needs to be optimistic, energizing children with their enthusiasm. I wanted to be close to my students and provide them with the best learning environment possible. With the introduction of the subway-school, we've returned to these kids the childhood they were deprived of.”

Parents were concerned about the potential dangers of the journey to school, as shelling could still occur en route to the underground station. Consequently, some families opted to continue with online learning. Olga Kuzeva, the mother of one of Anna Neelova's students, recalled initially being against the idea of offline classes:

“No one could quite grasp how this would work. There was a misconception that children would simply sit on platforms between trains. Even now, some people hold onto that belief. When I tell friends in Kyiv that my child attends a subway-school, they react with astonishment: 'In the subway? Right on the platform?' I had the same image initially: cold floors, marble. We declined the offer. But when we learned that Anna Sergeevna would be teaching in the subway rather than online, we changed our minds — we simply followed our teacher.”

Families who embraced the experimental project noted that although the underground classes presented a departure from the norm, the children, being with their peers, became more socially engaged and smiled more frequently.

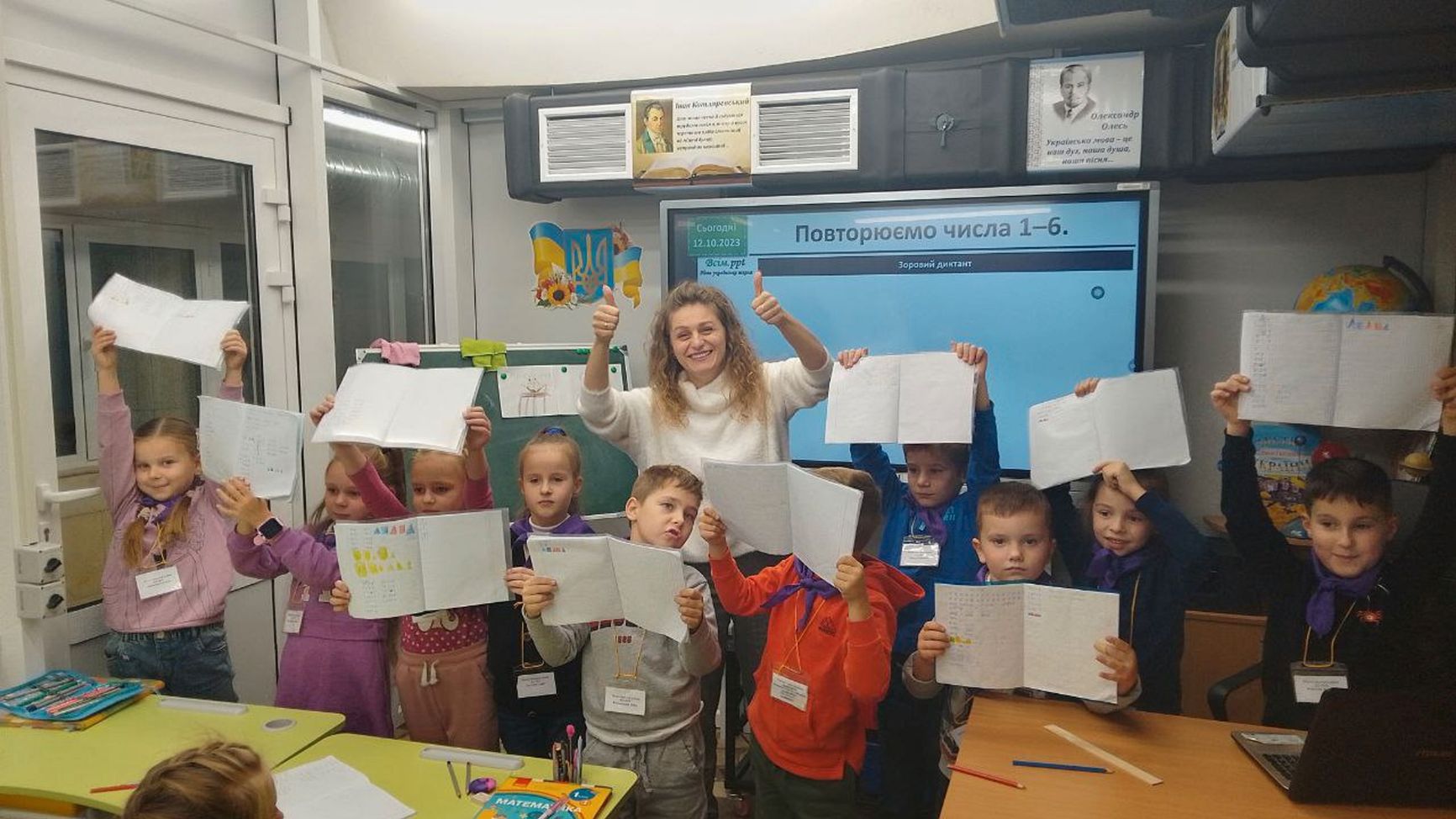

Anna Neelova with children

Photo: Anna Neelova

The lyceum where Neelova teaches was among the pioneers in initiating classes in the subway. Inspired by its success, other educational institutions in Kharkiv followed suit. Another teacher recounts:

“Once everyone witnessed firsthand the comfort and joy the children experienced, there was no doubt left. Children, unlike adults, cannot feign their emotions.”

Classrooms were established at five subway stations: “Pobeda,” “Universytet,” “Metrostroitelei,” “TraktornyiZavod,” and “Akademika Pavlova.” Initially, 60 classes were formed from over a thousand students, but over time, the number of participants in Kharkiv's “underground” education rose to 2,200. “Parents who were initially hesitant later regretted their decision and eagerly awaited openings to enroll. No one had anticipated such resounding success,” says Kuzeva, the mother of a subway-school student.

“When the classroom is quiet and the children are writing, you can hear the train noise”

The classrooms in the subway were set up in service areas located above the actual passenger platforms. Inside the rooms, soundproofing materials, along with air circulation and heating systems, were installed. “When the classroom is quiet and the children are writing, you can hear the train noise, but it's almost imperceptible and doesn't disturb anyone,” teacher Neelova says.

According to Olesya Fedirko, the mother of a second-grader, concerns about soundproofing worried many parents:

“We were concerned about how the children would study, but my son says that the noise from the trains is barely noticeable, and he can hear the teachers and everything that's happening around him perfectly well.”

After the second lesson of the day, students are provided with free meals — lunch boxes with sandwiches, vegetables, fruits, and juices. Additionally, each subway station has water coolers, restrooms, and a medical office. Anna Neelova says that the children in the subway classes are warm — they all remove their coats. However, unlike in regular school, no one wears indoor shoes.

“In the 'classrooms,' there are marble floors and nowhere to store shoes, so in winter, the children don't change shoes. But no one feels cold. Many pessimistically claimed that the students would be uncomfortable: cold floors, no natural light, but now, nobody is scared of that anymore,” adds Kuzeva.

The classrooms in the subway-school closely resemble a regular learning environment: there are desks, interactive whiteboards, and children with books and notebooks. “My son loves the subway-school. He is especially attracted to the colorful desks They were the same ones he had in kindergarten when he used to attend,” says Olesya Fedirko, another Kharkiv parent.

Children in a subway classroom

Photo: Kharkiv city council/Telegram

Children and teachers learn about shelling incidents through messages from parents. “In such cases, parents write to me to give a heads-up. Once, we waited for an hour like that, but being in the subway, there's always something to keep the children occupied: playing with them or watching a movie,” the teacher says.

After a long period of remote learning, transitioning back to in-person classes proved challenging for students. Many saw the subway classrooms as a place to play and socialize with their peers. However, teachers quickly re-established the learning process. Olga Kuzeva reveals that her daughter eagerly anticipates returning to school every day and dislikes online classes:

“My daughter loves learning and enjoys socializing. First, there was COVID-19, then the war. Our children grew up without the collective and the necessary social environment. My daughter loves the subway school so much that I often use it as leverage when she misbehaves. I say, 'If you don't eat, you won't go to school,' or 'If you don't do this, you'll stay home.'”

Despite students’ satisfaction with the atmosphere of the subway-school, they still look forward to the day when life will return to something approximating a pre-war, pre-pandemic normal. When congratulating classmates on their birthdays, the wishes they offer are not for “happiness” or for “lots of presents,” but for the opportunity to return to their regular school above ground, says teacher Neelova.

Anna Neelova with students

Photo: Anna Neelova

In the subway-school, classes are attended by students from elementary, middle, and high school levels. To enroll in the “underground,” students must be attached to a so-called “backbone school,” where children from various districts are temporarily assigned. These students form special classes designated with the letter “M.” However, the majority of students are younger children, as they require more socialization. They have more offline classes — three days a week, compared to two days for older students.

The majority of students are younger children, as they require more socialization

Olga Kuzeva says that her daughter eventually had no trouble adapting to the in-person classes, but initially it was a rarity for her to sit through such lessons without getting distracted — or tired:

“My daughter could stand up in the middle of a lesson and say, 'I'm tired of writing, I'm going to lie down.' And she would get up, walk around, lie down. There's a corner in the classroom with soft bean bags, and she would settle there. Each child starts studying in their own way. But now it's better: all the children are true students — they know the routine, schedule, and behavioral norms.”

On weekends, the subway classes transform into a subway-kindergarten, where preschoolers who will enter school the following academic year gather to get accustomed to what — with no end to the war in sight — will likely be their reality come September. These sessions are organized to help future first-graders adapt. According to the teacher, it was more challenging to establish a connection during lessons with children who hadn't attended kindergarten for two years compared to those who were already socialized.

Wartime curriculum

The curriculum during wartime at the subway school focuses on subjects that require more hands-on practice and contact with teachers. Younger students study Ukrainian language, reading, and mathematics, while older students have a wider set of subjects. Typically, all students at the subway school have three lessons per day, with additional online sessions available. These additional sessions usually cover creative disciplines, such as music or art.

A significant emphasis is placed on psychological support. During the first six months of the subway-school experiment, the lessons aimed to alleviate stress and anxiety among the children. As Neelova explains:

“Each child has their own story. Some have experienced shelling, while others, like the children from the Donetsk region who joined us, have long lived under stressful conditions.”

During the first six months, the lessons aimed to alleviate stress and anxiety among the children

To alleviate the psychological strain, representatives from UNICEF visited the subway-school, where they conducted a special session called “Facing Our Fears” that involved children drawing what scared them and then openly discussing the resulting pictures. According to Neelova, this practice is crucial, as it allows students to vocalize what troubles them. Initially, many children would suddenly burst into tears or hide under their desks.

During lessons, children often spoke about their fathers who were fighting or reflected on why “they attacked us.” The teacher describes how her role in such discussions has evolved: “I used to think my task was to shield them from these conversations, but now I understand that they need it. Children feel better when they verbalize their fears.”

Olga Kuzeva says that her daughter already “subconsciously reacts to danger.” She explains, “Children are aware of the anxieties, the rockets, and why we sleep in the corridor. When we went to Bulgaria for two weeks, and I went to tuck her in at night, she immediately woke up and said, half-asleep, 'Alert, right? Should we go to the corridor?' I thought the child hadn't been noticing anything—we tried to quietly move her to a safe place during nighttime air raids. But she already understands everything.”

Patriotic themes form a significant part of the school curriculum. On the Day of Unity of Ukraine (January 22), students engaged in discussions about what it means to be Ukrainian and the importance of “unity.” Similarly, on the Day of the Coat of Arms (February 19), children showcased their drawings to the teacher via Zoom. Even when holidays provide a day off from classes at the subway-school, students still take a moment in the morning to listen to the national anthem, placing their hand over their heart.

Another crucial aspect of education involves sessions on landmine safety. Teachers provide valuable insights into identifying potentially explosive objects, emphasizing that ordnance can be encountered anywhere in Ukraine.

Teachers provide valuable insights into identifying explosive items and their appearance, emphasizing that ordnance can be encountered anywhere in Ukraine

Additionally, classrooms often host physical activity breaks, known as “fitness minutes.” One of these sessions, called “Victory Soon,” aims to teach children to focus during moments of danger. It emphasizes that air raid alerts should not instill fear, but rather prompt action — namely, taking cover.

In November 2023, the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, paid a visit to the subway-school. Anna Neelova recalls the surprise of the children, with younger ones initially failing to recognize the head of state. She recounts the moment: “We were in the middle of a math lesson, and there was a fitness break. I stopped it and said, 'Look who's come to visit us. Do you recognize him?' They are still young and didn't understand at first. One of the students said, 'I think I've seen him. Is he the president?' — and at that moment, the children burst into laughter.”

President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky with children during his visit to the subway school.

Photo: Anna Neelova

On April 2nd, another significant project for students was completed in Kharkiv — the construction of a fully-fledged underground school. Development began in October 2023, and now the underground classrooms are ready to accommodate around 900 students. Enrollment lists for the next academic year are already in place. In a policy decision that says much about Ukrainian authorities’ expectations about how long the ongoing war might continue, Kharkiv Mayor Ihor Terekhov says there are plans to construct several more such schools in the near future.